|

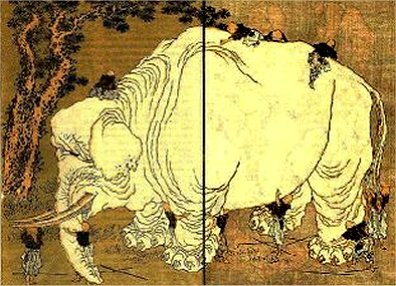

The Evidence of Things Not SeenIt's easy to get exasperated, if not overwhelmed, with the minutiae of bookselling. There's so much of it, for one thing - actually, too much. For another, some of it's maddeningly complex. Making lists of collectible titles, publishers, authors, illustrators, first edition designations, etc., can transform you into a power bookseller in time, but there's really no end to it. Even a lifetime of learning will never get you to anything resembling a final destination. Still, to be successful, there's no choice but to acquire as much knowledge as you possibly can and, particularly if you're new to this business, in the shortest time possible. Since nobody does or can know it all, however, it may seem futile to apply any deliberate and consistent effort to the task, far more sensible to rely on the process of buying and selling books for your education, even if it is by osmosis. If I had to guess, I'd say that, in practice, almost nobody in this business regularly sets aside time to acquire bookselling knowledge, and if there are those who do, I seriously doubt that many of them would adhere to a logical plan of action or course of study. Most of us acquire our knowledge on the fly, in the process of being booksellers - buying and selling books - and rarely take time (or think we have it) for focused study. Sadly, we're less than we could be because of it. There's irony here too, a point at which you can sell too many books, come to a place where you'll flatten out in knowledge or even get dumber because you'll be spending so much of your time on the peripheral aspects of the business (interaction with customers, fulfillment, recordkeeping, etc.) and less on the books themselves. This is why most of the most knowledgeable sellers are also high-dollar/low-volume sellers. They spend time with the books they sell. Learn them. Then make more money when they sell them. If there's any learning at all going on outside the process of buying and selling books, it's probably by way of reading forum notes or talking to other booksellers, which, depending on who's doing the talking, may or may not be productive sources of information. Even if good information is shared, it's at best haphazardly delivered, like throwing multi-colored confetti into the air. Gathering up the reds and blues, etc., as they flutter down, sorting things out, is all but impossible. Some forums (eBay's bookseller's forum comes to mind) make heroic efforts to archive topics on the basics of bookselling, but they often read like Kerouac on permanent leave - a kind of stream of (sub)consciousness that has at best a vague source or beginning, a wildly meandering course, and certainly no discernible mouth at the end. BookThink's answer to this lovable mess is, as you may already know, flashpoints, those exquisite details that indicate value in books you've never seen before or have any prior knowledge of. (Click here for detailed discussions of flashpoints.) Flashpoints are something that most definitely can be acquired and learned deliberately, and while there's no end to these either, if you concentrate on learning those with the widest applicability first, I think you'll be amazed at how fast you can get book smart. I referred to widely applicable flashpoints in an earlier issue as a form of expansive knowledge - knowledge that, once acquired, expands in your mind. Concentrate on acquiring expansive bookselling knowledge first, that is, and you'll grow by leaps and bounds. Until now, I've come at this from a positive direction, looking at how flashpoints can be used to identify valuable books. Today, however, I'm going to approach this from a different, more negative direction, first by looking at some things that can't be seen and showing how the un-seeable can help us see, second by introducing the concept of antiflashpoints - details we can plainly see that indicate worthlessness. It's important to know how to buy valuable books; it's also important to know how not to buy worthless ones. Apart from the money we waste on them, they also cost us valuable time in research and disposal. For this discussion, the ancient Buddhist fable of the six blind men and the elephant, here retold by 19th century poet John Godfrey Saxe, is a good place to begin:

The stated moral of this poem, that each of us sees only part of the truth and should keep this in mind, make allowances for it when interacting with others (who, in turn, see different parts of the truth than we do), is straightforward and readily grasped. But there's a deeper lesson here that's often missed. The poem was written for us, not the six men of Indostan, and the truth is that most of us aren't at all blind, not clinically anyway; we can see pretty well. Thus, provided we don't stand too close, most of us can see at least half of an elephant at once, and if we're standing on one side of a specimen, we can readily extrapolate things, assume that we'd see much the same thing if we were standing on the other side. And we'd be right. It might be more difficult to extrapolate to tarpaulin-sized ears, ivory tusks or a trunk if were we standing at the back end, nose-to-nose with the elephant's swishing tail, but even then past experience would probably suggest that there's likely to be at least a head, eyes, ears, and so on, up front, and tusks would not necessarily be something we'd be surprised to learn of if we also had knowledge of, for example, rhinoceroses. Given the similarity of a rhino's hindquarters to that of an elephant's, we might even surmise something horn-like, though likely we'd guess at one horn, not two, and be wrong altogether about tusks being horns. There are flashpoints for big game hunters too, and clearly ivory tusks qualify as flashpoints in spades, but flashpoints on animals (as well as on books) aren't always easily spotted. Like blind Indostans, though we look, sometimes we don't see. Animals are often camouflaged by their environment. So are books. Put an exotic book in with some ho-hums, and it might be all but invisible. One of the most valuable lessons I was ever taught about deer hunting was not to look for deer at all but for branches that resembled antlers - and sometimes a deer might be attached to them. The equivalent lesson for booksellers is, don't look for valuable books; look for flashpoints, and good books may follow. This kind of seeing, the capacity to extrapolate from parts to wholes, can be powerful, even in bookselling. If we look for tusks, that is, can elephants be far behind? But what if there are no tusks to be seen? And no elephants? Can we extrapolate to them anyway? Take an estate sale you've arrived late to. Or an FOL sale. Let's say there are bookcases lining the walls of a room and perhaps many 100's, maybe 1,000's of books, remaining. No blockbusters (elephants) in sight, but, here and there, there are gaps. Places where books obviously were. Or books fallen over because supporting books are no longer supporting them. No accumulation of books would've looked like this if it hadn't been recently ransacked. The only explanation is that books have been sold. If not entirely elephants, no doubt plenty of lesser (though still valuable) game. You've been left with a field of small, furred rodents. Your first instinct at seeing a book sale hunted out might be to turn and leave, but if you're new or relatively so to the sport of book hunting, it could be very instructive to stay for a few minutes and study what's left. Believe me, almost nobody does this kind of thing, and there may be much to learn both from the evidence of things not seen, not to mention the junk that's left over. Consider numbers first. Unless it's a very unusual sale, chances are most of the shelves are still relatively full of books. This should tell you - and perhaps this is too obvious by half for most of you - that books with value are remarkably few in number, but it should also tell you something else that's not widely appreciated: books that do have value are most often found in the large, sometimes obscuring company of worthless books. Camouflaged. The gaps confirm this time and time again, as will your own experiences at sales you arrive early at. In Bookland, you don't have to travel to Africa to find big game. It's everywhere, sometimes in the most unlikely places. Also look at gaps. More often than not, if people have large numbers of books, they arrange them, group them in an intuitive manner, usually by subject or author. Look at where the gaps are. Then look at the books that stand nearby or actually form the gaps. There's a good chance that they will suggest some things about the books that are no longer there in the same way that two parts of an elephant might suggest an intervening part. A shelf with numerous books missing may be especially revealing. Make mental notes of what you see; make a habit of doing this at all big sales you arrive late at; and in a relatively short period of time you'll get very, very smart about books, know what's topically, flash-pointedly valuable, without ever having seen the books that were sold. Look also, of course, at what you can see. A good exercise is to look for books that you'd probably buy at any time and any sale, not on the basis of having specific knowledge of their value but on the basis of their apparent value. Since you know going in that it's very likely that everything left in the room is worthless, try to figure out why books that interest you don't have value. Do this also with the ones you do buy. Don't just toss them aside in disgust. Here are some specific things to look at, some obvious, some perhaps less so:

< to previous article

Questions or comments?

| Forum

| Store

| Publications

| BookLinks

| BookSearch

| BookTopics

| Archives

| Advertise

| AboutUs

| ContactUs

| Search Site

| Site Map

| Google Site Map

Store - Specials

| BookHunt

| BookShelf

| Gold Edition & BookThink's Quarterly Market Report

| DomainsForSale

| BookThinker newsletter - free

Copyright 2003-2011 by BookThink LLC

|

|