|

A World Class NicheIn Collector Land, there are niches, and there are niches. Some are narrow, sharply focused on a single author or a topic so obscure or taboo as to be almost hidden from public view. Others are broader. Some are so broad that it's tempting to subdivide them into sub-niches and attack them separately. The problem with this is that sometimes we unwittingly excise the forest from the tree - that is, in the attempt to define the tree we focus on it to the point of forgetting the forest altogether, and yet it's the forest that ultimately gives meaning to the tree. Example? Suppose you're book hunting, and you spot a copy of Betty Crocker's Microwave Cookbook at a thrift shop. Never having encountered the thing before, you think, "Well, it's in splendid condition, and since it's only a buck, why not take a chance on it?" Okay, you buy it, take it home, search the title on Amazon Marketplace, and discover to your considerable dismay that as-new copies in dust jackets start at a budget-friendly $.01. "Damn," you then think, "I'll never buy that book again." Fine, but how much knowledge have you gained for your buck? Not much, considering that thousands of other microwave cookbooks have been published as well. What's to prevent you from buying The Good Housekeeping Illustrated Microwave Cookbook the very next time you visit a thrift shop? Nothing - yet. You'll buy it for the same reasons you bought the first one, haul the piece of crap home, and discover it's a loser too. How many additional microwave cookbooks will you have to buy before you stop buying them? 5? 10? It will no doubt vary with every bookseller, but I think you'll agree that this isn't a very efficient method for getting to the ultimate conclusion that all microwave cookbooks are losers, and, besides, how would you know that, if you bought 49 dogs, the 50th wouldn't be a winner? Until you understand more about microwave cookery (and I'm using the term "cookery" loosely), you simply won't know when to give up because, when you use the inductive method - when you seek conclusions based on the evidence you've gathered - you don't know when to stop gathering evidence. The deductive method attacks this much differently. You start with the conclusion and seek evidence to confirm it. If the conclusion is based on certain and profound knowledge, it can be startlingly effective, not to mention efficient. Using the above example, once you know that microwave ovens have the capability of transforming perfectly good steaks into gray rubber, it's a short leap to the conclusion that microwave cookbooks, even at a penny a throw, are obscenely overpriced. In this case, you don't even spend the first buck. So far, so good, and this takes us back to niches. Broad ones. There are very few broad niches that can be categorized as hot, but one bright exception is the Arts & Crafts movement in America. It's hot now; it's been hot for years. No question that this movement had strong international expression as well; in fact, it originated in England with, most agree, John Ruskin and a contrary group called the Pre-Raphaelites in the 19th century. I'm going to stay primarily on this side of the Atlantic today, however, because that's where the bigger money for booksellers is, in the same way that an antique Pennsylvanian desk will, almost inevitably, outperform its European relative. The Arts & Crafts movement is a broad niche today because, at its peak, it was remarkably pervasive, coloring myriad aspects of everyday life, especially those closest to home - the home itself, in fact. The house. Its contents. Its grounds. Understandably, a significant quantity of pertinent literature survives. Books, periodicals, catalogs, ephemera, etc. No doubt some or all of the following flashpoints will sound a familiar note: Stickley, bungalow, Roseville, kit houses, Roycroft, Alladin Readi-Cut, mission furniture, Prairie Style, Tiffany, quarter-sawn oak, Louis Sullivan, etc. Arts & Crafts generated - one and all. There are 100's more, many of which will appear in today's Premium Content. Before I get to the nuts and bolts of what to look for, I think it's important to understand at least something about what this movement was about. Take a look at the forest, that is. Its stated principles. How it started. Why it dominated American life until World War I. In short, use the deductive method. This knowledge will greatly increase your ability to both identify multiple manifestations of Art's & Crafts expression in books and ephemera and, in turn, market these items for maximum profit. No rubber steaks. A good place to begin this examination is with Brits John Ruskin and William Morris. First, Ruskin. Though notorious generally for an affection for young girls and specifically for a late-life disappointment with one Rose la Touche (which had its denouement in a mental breakdown), Ruskin was perhaps the most influential art critic and social theorist of the Victorian era.

Ruskin, a sometimes artist himself, anointed the Middle Ages (of all things) as a sort of golden age of art because of its direct, intimate relationship with nature. Here's the skinny: nature expressed through man as art was moral. The central problem of the Victorian era, by contrast, was the machine, how it separated humankind from nature, enslaved workers, and ultimately dehumanized them. Anything produced by a machine, Ruskin declared, was inherently dishonest. Historically speaking, what this reduced to was an antidote to the ravages of the Industrial Age. Whether you agree with any of this thinking or not, there were indeed ravages, and it was inevitable that a counteractive movement of some ilk would emerge. Enter painter/designer William Morris. Morris put Ruskin's thinking into action. He, like Ruskin, loathed Victorian design, its gone-mad, miles-over-the-top ornamentation, massed admixture of styles, fussy delicacy, etc., and he was acutely disdainful of things cranked out by - no surprise here - machines, especially things produced for no other purpose than to function as decorative elements. Morris also had a deep affection for the Middle Ages, notably the concept of craftsmen's guilds, which by their very nature united "head and hand" - in other words, Middle Age craftsmen served as both designers and manufacturers, painstakingly producing inspired one-offs, and thus the process of production was a moral, character strengthening event. In 1875, Morris founded Morris & Co., a guildsmen-organized manufacturer of furniture and decorative accessories (e.g., stained glass, wallpaper, etc.), and later the storied Kelmscott Press, which published, among other things, stunning examples of his own writing, illuminating the concepts he lived and breathed. Kelmscott Press productions were based on the principle of the "whole book," an approach which aspired to integrate a book's form with its content, thereby producing a unified, eye-popping work of art. If you've ever felt a vague dissonance reading, say, War and Peace or another patently great book in a pulpy, mass-produced format, you know only too well what Morris' whole books were not. Handmade paper, dark black (red accented) ink, vellum bindings, woodcut illustrations - these were active elements, and they spoke quality at every turn. (By the way, stumble into a Kelmscott Press production at a garage sale, and you'll be able to winter in Aspen next year.)

In one sense, both Ruskin and Morris can be viewed as progressive (if not revolutionary) in their thinking. What they were proposing and to some extent doing was shaking the very foundations of society. And yet they also believed that a return to pre-Industrial Revolution days would restore society to its former health. In this latter sense they were most decidedly reactionary, and to some extent this explains why the Arts & Crafts movement in Europe wasn't the explosive force it ultimately became across the Pond, specifically, in a brash, vigorous country where it made perfect sense to embrace the advances of the Industrial Age, to use machinery itself to produce art - America. The American Arts & Crafts movement didn't get out of the blocks until after Morris' death in 1896. Two prominent names come to mind here as well - Gustav Stickley and Elbert Hubbard. In 1901, Stickley founded The Craftsman, a magazine that would serve brilliantly as a platform for teaching and advancing the principles of the Arts & Crafts movement. Stickley, heavily influenced by Ruskin and Morris, believed in self-reliance, individual initiative, creativity, etc., but also saw that technological advances could help further these ideals, not undermine them. What Stickley is best known for, of course, is furniture, and though his workshops were also organized as guilds - craftsmen were actively involved in the both the design and production processes - machinery was utilized to a significant extent. Hubbard, also a pioneer of the Arts & Crafts movement in America, founded Roycroft Printing in 1895 - a deliberate attempt to emulate Morris's Helmscott Press. He became wildly successful as a publisher, editor and essayist, and so many visitors flocked to his shop that he built an inn to accommodate them. Within a year or so, the inn evolved into a thriving community, and the Roycrofters began to produce furniture and other items as well as books, among them the well-known Morris Chair.

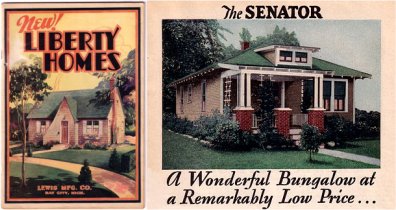

What is the Arts & Crafts Style?Human nature can be fickle, periodically discarding trends, fads, etc., simply because it's time for something new. No doubt this drove, in part, a growing disenchantment with Victorian style in the late 19th century, but there was a reason why Arts & Crafts in particular supplanted it in early 20th century America. Family life was changing. More and more, men left home every day to go to work, and, as servants became less plentiful and affordable, women (if they weren't leaving for work themselves) stayed home to care for their children, assuming the role of primary homemaker. As the home became, essentially, a one-woman operation, something smaller and more efficient was needed. Sprawling Victorian estates with huge porches, servant's quarters, parlors, conservatories, and so on, became utterly impractical for many middle class families. Instead, the small, efficiently designed Arts & Crafts inspired home served their purposes much more effectively. Adornments were minimal, inside and out, and landscaping was inspired by nature itself - that is, native plants were used and often allowed to grow with near abandon, sometimes in intimate contact with the home's foundation. The "wild garden" was born. Defining the Arts & Crafts style is difficult to do with much precision or consistency, but here are some common tendencies: vertical and often elongated forms, clean lines, repetitive design, and (not always present) a neo-Gothic tone. Here's a Craftsmen house from a catalog:

A book colonnade from a Craftsmen interior:

And a lamp:

The more Arts & Crafts examples you see, the better you'll be at spotting the books, etc., that will pertain to the movement - and bring you the biggest profits. We have the good fortune of living in the midst of an A & C revival in America. There's enormous appeal in this stuff, and there's still a lot of it around. Take advantage of it while it lasts. Today's Premium Content will show you how.

Questions or comments?

| Forum

| Store

| Publications

| BookLinks

| BookSearch

| BookTopics

| Archives

| Advertise

| AboutUs

| ContactUs

| Search Site

| Site Map

| Google Site Map

Store - Specials

| BookHunt

| BookShelf

| Gold Edition & BookThink's Quarterly Market Report

| DomainsForSale

| BookThinker newsletter - free

Copyright 2003-2011 by BookThink LLC

|

|