|

Kangaroos to Climate Change

|

|

Dr. Tim Flannery's achievements bring to mind the great 19th-century adventurers. In fact, Sir David Attenborough is quoted as saying "Tim Flannery is in the league of the all-time great explorers like Dr. David Livingstone." One particular accomplishment stands out: Thirty new species of mammals, including two types of tree kangaroos, were discovered and named by him.

|

|

|

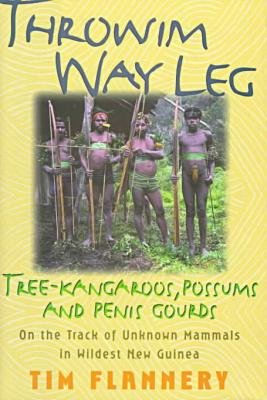

This intrepid explorer is an ardent conservationist who has won international acclaim as a scientist, writer, and engaging public speaker. You may be familiar with his regular contributions to the New York Review of Books and the Times Literary Supplement, or you may have heard him on NPR or the BBC. Tim Flannery is one of Australia's leading thinkers and writers. He currently serves as director of the South Australian Museum, chairman of the South Australian Premier's Science Council and Sustainability Roundtable, director of the Australian Wildlife Conservancy, and is the National Geographic Society's representative in Australasia. His writing is intelligent, honest, and thought-provoking and can also be delightfully humorous. His books span subjects from the ecological history of Australia and North America, to descriptions of rare and extinct mammals, to the causes of - and solutions for - global climate change. Through his lucid writing and public speaking, he helps us understand the very real danger of global warming and encourages us to be optimistic and action-oriented. I confess that I am in awe of this man, but I was not surprised to find that he is a delightful person to talk with and humble in spite of his many accomplishments. After all, he has experienced the company and culture of primitive people in the most remote environments, and in the course of his explorations, he has crawled through dark bat caves, slept in rain soaked lean-tos, suffered odd food and disease, yet written about it all quite cheerfully. I would like to think author Sharon Vanderlip for introducing me to his work and his writing. For more information on Vanderlip, see this BookThink's Author Profile. As I spoke with Tim, he was nearing completion of a U.S. speaking tour. BOOKTHINK: First of all, thank you for sharing your knowledge and your life of adventure and exploration through your writing. Let's start with a little bit about you. When did it first occur to you that you could have such an extraordinary life and career? Did anyone ever discourage you from this path? FLANNERY: They did. I was one of those kids who was always interested in nature. I was not the world's best football player or the world's best academic, but I was very interested in the natural environment. I couldn't think of what to do at the end of school, so I thought I'd go to university and study to be a high school teacher. Back in those days, the state government would offer you a scholarship to pay your way through university if you pledged to teach for three years. I got to the end of my university time and was thinking about going to the classroom, and I thought, "I can't do this." I trooped up to the education department and talked to this man. I said, "Look, I just can't do it," and he said, "You are making the biggest mistake of your life. This is a meal ticket for life if you become a teacher. If you don't become a teacher, you'll have to pay it all back, you know." And I said, "Yes, I know, I'll pay it all back." And I did. I went on and did my MSC in Geology, and I was really much more interested in that. Then I went on to do a Ph.D. in Biological Sciences and was just lucky enough to get a job in a museum. I was very fortunate that a Californian, Dr. Tom Rich, had sort of taken me under his wing when I was a student and allowed me to do volunteer work in Melbourne where I grew up. He was really my mentor, the person who made it possible for me to think I might have a career like this. BOOKTHINK: It is great to hear a story like this. I work in the Career Services Office at a local college, and so many times I'll hear a student say, "I want to be an anthropologist" - or a zoologist, or a similar career - and someone, somewhere, will usually try to influence them against it, saying it's not practical, it won't take you anywhere. FLANNERY: Some of us do jobs that don't really have a name. You've just got to follow your style. That's what I've learned through life anyway. Follow your style, do what you really want to do, and that way you'll at least be a little bit good at it. BOOKTHINK: In reading your books, I begin to realize how many areas of knowledge and understanding have to come together to form a picture of life on earth: environmental science, zoology, anthropology, climatology, languages -and I wonder how you do you do it all? It strikes me that you must be a very curious and resolute person, with a mind like a sponge, to have acquired all this knowledge. FLANNERY: That's one thing my brain has always performed a pattern of doing. I've always tried to build up a big picture, a satisfaction of how it works at that level. I'm very, very happy chasing down information, even if it feels a bit foreign, even if it means I've got to learn by asking a lot of questions. I'm thick skinned enough that I don't mind asking stupid questions of my colleagues. I've got to admit to them, it's not my field, but can you tell me or teach me what the significance of this is, even if it sounds a bit dumb. I've always been a bit like that I suppose. Nothing gives me satisfaction like that moment when you suddenly see the links between things and understand how something works. BOOKTHINK: You must have incredible energy. I was looking at your lecture schedule, and that alone is daunting. FLANNERY: It's beating me! I'm running out of energy. But part of the enjoyment is meeting all these wonderful people. I've just been to the South Carolina state legislature, where they've got a committee dealing with climate change. And it was just so wonderful interacting with those people because you feel you can give something to them. They were very interested in what we are doing in Australia in terms of our energy policy and everything else. That sort of thing energizes you because you feel you are doing some good. BOOKTHINK: Does it give you hope? FLANNERY: Oh, yes, it does. There were a huge number of people of good will there that day. What we really need now is some good information and direction and energy. BOOKTHINK: Have you had time for any of the more regular things in life - like a family - or has your life been dedicated pretty exclusively to research, exploration and writing? FLANNERY: I do have a family. I've got a son who is 21 and a daughter who is 19, and it's been lovely - I have all of that. To be honest with you, this last year has been the toughest year of my life in that I've spent more time away from my family than ever before because of the demand for information. That's the price of doing this, I suppose. BOOKTHINK: I guess the one good thing is that we have technology to keep in touch with people. It's not quite like when Sir Richard Burton when off into the wilds. FLANNERY: Exactly true. It's a great blessing that we can do that. And we can get home quite quickly. It's not a six-month sail to Australia anymore. BOOKTHINK: The first of your books that I read was Throwim Way Leg - a delightful journey with you as you introduce the reader to remote creatures and people of New Guinea.

It left me with a feeling of optimism, that the age of exploration on earth is not finished. FLANNERY: Well, you see when I was doing that (early 1980's), it was like Sir Richard Burton. There weren't satellite phones or GPS systems when I started there - we were just there, in the bush! It was wonderful. It came home to me when my student recently went to a very remote area that I'd always wanted to get to, but we just couldn't when I was in the area because we couldn't get the helicopter time. He went there and called me from a mountaintop using a satellite phone - which was incredible. BOOKTHINK: Can a young person today still look forward to being an explorer, to making new discoveries on earth? FLANNERY: Yes, well, we've got a museum full of them in South Australia. We've got one guy who has just come back over the last twelve months from exploring the last unvisited mountain range on earth, which happens to be a submarine one, in the South Pacific Ocean - it is south of Easter Island. He goes down in Alvin, the submersible. Imagine being the first person to see that mountain range, you know? The images he brought back were incredible, the photography was amazing. When I first started doing all this work, I thought the age of exploration was over. I thought, "Well, there've been so many people working in New Guinea, maybe I'll be lucky to be able to describe some new kind of rat or something that someone's overlooked." It turned out to be completely the opposite - there was a whole world out there that no had looked at. BOOKTHINK: You have discovered and named many new mammal species. What has been your most exciting or personally satisfying discovery? FLANNERY: I think the discovery of that black and white tree kangaroo, the Dingiso (Dendrolagus mbaiso), was the most amazing thing for me. An animal the size of a Labrador dog, as strikingly colored as that - that it could have remained undiscovered until 1995 seemed incredible. That was quite something to think, "I'm the first European to see this thing." Having the pleasure of describing it and figuring out a bit about its ecology and studying it was wonderful. That really was the high point for me - of my biological career anyway. BOOKTHINK: Any intriguing places you would still like to explore? FLANNERY: Oh, yeah. Just from a strictly scientific perspective, some of the mountains of west Papua still beckon. The trouble is, when you get past 40, the mountains just keep getting taller and taller and steeper and steeper. BOOKTHINK: I'm curious about the recent discovery by an Australian team of the bones of a species of small, hobbit-like human beings that lived in the islands of Indonesia. What do you know about this? FLANNERY: That was the most amazing discovery! One of my very closest friends made that discovery. He told me about this when they made the discovery and I thought, "Well, I'm sure it can't be what he thinks, that it's just something a bit odd." Then, well before it was published, he sent me a copy of the findings. It was about April, and I remember thinking, "Is this an April Fool's Day joke? It's too elaborate. It can't be." But as it turns out, this is one of the most amazing discoveries made in the 20th century. And when it was published, of course, it was amazing to see the reception it got. Those little people, they were less than a yard high and weighed only as much as a 3-year old child. Can you imagine them living on an island alongside Komodo dragons and pygmy elephants and giant rats? BOOKTHINK: It's fascinating to read about the indigenous people and tribes you have come across in your travels. I loved the story in Throwim Way Leg about a man you came in contact with who was familiar with flashlights, but was amazed at the sight of a candle because it was an innovation that had passed them by. FLANNERY: That's true for those people. They think nothing of getting into a light aircraft and flying, yet when they see a bicycle they always fall over with surprise. BOOKTHINK: How important is it that the world still is peopled with human beings who have different cultures and world views - and is that doomed to be a thing of the past? Are we all going to be completely homogenized? FLANNERY: That depends on a great deal. There's been a process of homogenization so far, but the world is full of forces that drive that homogenization and also serve to break it up. I just feel enormously privileged that I've lived in a time when I could contact people whose ancestors last had anything to do with mine over 60,000 years ago; where we've had 60,000 totally separate years of evolution. Nothing like that will ever occur again. So what we are seeing is the outcome of what it really means to be human. Those people who come from as different cultures as we could imagine still recognize a smile and a frown and can still communicate even in the absence of language. I find that miraculous. It is a strong testimony to the essentials of humanity that we all share. BOOKTHINK: You have seen many changes in regions you have explored during your career. What are some of the biggest changes you have seen - for the bad and the good? FLANNERY: Goodness. Well, I've seen some of the people of the world go from basically sort of a Stone Age existence fully into the modern world. I suppose it came home to me at the Ok Tedi Mine when I was there in 1985. I worked with an extremely knowledgeable old hunter a very traditional man called Serapnok. There's a picture of him in the book [Throwim Wayleg]. He was very distinctive looking, with a big hooked nose, and I became very fond of him. I visited the mine again later and couldn't find Serapnok. He was out in the bush. But I was getting a helicopter ride - the helicopter pilot was a young Papua man, and I looked at him and saw the nose and asked, "Do you know Serapnok?" and he said "Yeah, he's my dad." "You are a helicopter pilot for the mine?" "Yeah." In one generation, they'd gone from absolutely traditional bush hunter to helicopter pilot.

|

| Forum | Store | Publications | BookLinks | BookSearch | BookTopics | Archives | Advertise | AboutUs | ContactUs | Search Site | Site Map | Google Site Map

Store - Specials | BookHunt | BookShelf | Gold Edition & BookThink's Quarterly Market Report | DomainsForSale | BookThinker newsletter - free

Copyright 2003-2011 by BookThink LLC

|