|

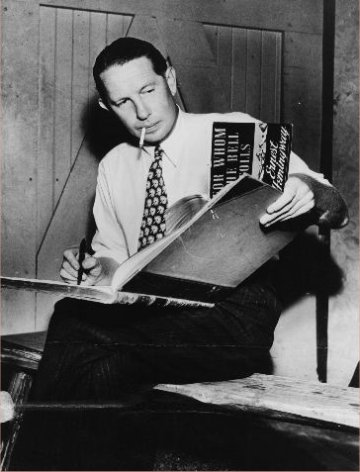

Louis Bromfield

|

|

Novelist, short story writer, political writer, playwright, scriptwriter, essayist, journalist, soldier,

innovative farmer, nature writer and conservationist: Louis Bromfield was all of these, and more.

Awarded the Pulitzer Prize for fiction in 1927 (Early Autumn), the O Henry Memorial Short Story

Award in 1927 (The Scarlet) and 1928 (The Skeleton at the Feast), and membership in

America's National Institute of Arts and Letters (1928), he wrote prolifically. He received

the Audubon Medal for leadership in conservation farming in 1952.

|

|

|

In 1980 he was posthumously elected to the Ohio Agricultural Hall of Fame and in 1996 (the centennial of his birth) a bust of Louis Bromfield was placed in the lobby of the Ohio Department of Agriculture's new headquarters in Reynoldsburg, Ohio.

Louis Bromfield was actually born Louis Brumfield. A typo in his last name by editors in one of his early works led to the writer's decision to change the spelling permanently. He was born in Mansfield, Ohio in 1896 to Charles Brumfield, originally from New England, and Annette Marie Coulter Brumfield, the daughter of an Ohio pioneer. He went to school in Mansfield, working on his grandfather's farm and as a cub reporter for the Mansfield newspaper. He attended Cornell University Agricultural College in Ithaca, NY from 1914-1915, then returned to Ohio when his help was desperately needed on the family farm. Later he enrolled at Columbia University School of Journalism. His career always straddled both the agricultural and the literary. During WWI, he left Columbia University to enlist in the U.S. Army Ambulance Service and served as a soldier with the French Army from December 1917 to February 1919. Fighting in seven major battles, he received the Croix de Guerre, the French military decoration for bravery in combat. When he returned to America to live in New York City, he began writing for various news agencies and other publications, including Musical America, Time Magazine, and The Bookman. He was married in 1921 to Mary Appleton Wood, a New York socialite of old New England stock, and they had three daughters. Ellen Geld Bromfield, his youngest daughter, went on to become an excellent writer and agriculturist herself - and warrants an entire article on her own work. She wrote several successful novels - her first novel was The Garlic Tree, Doubleday & Co., 1970, a story set in Brazil - as well as non-fiction books on Brazil, where she and her husband Carson created Malabar-do-Brasil, the South American extension of Malabar Farm in Sao Paulo, Brazil. Ellen is now 75 years old, still living in Brazil. She remains closely involved with Malabar Farm in Ohio, which she visits every two to three years, and is a continuing source of insight and information to the staff. She will be attending the Visitor's Center opening event at Malabar in September. Daughter Hope is 80 years old, still living in Montana where she and her husband have run a ranch and a wildlife sanctuary for many years. Daughter Ann, who suffered from schizophrenia, is no longer living, but her oil paintings still hang in the "Big House" at Malabar. While living in France (1925-1938), Bromfield became very much a part of the circle of American "Lost Generation" artists working in Paris. Ernest Hemingway, F. Scott Fitzgerald, Gertrude Stein, and other famous writers of the time often spent their Sundays at the Bromfield home. He and Edith Wharton found they shared a love of gardening and corresponded for years. While still living abroad in 1932 Bromfield, wrote The Farm, which many consider his greatest, most heart-felt novel. In it he wrote of Midwestern U.S. industrialists and short-sighted farmers who plundered the natural beauty and richness of the earth while building a society based on greed and materialism, filling the horizon with smokestacks and draining the soil of productivity, sapping humanity's spirituality and hope. One could read his depth of feeling in the book; he was homesick for his ideal country, the Midwest as he longed for it to be. It was a precursor to his return to America and to all that was to follow. In 1938, with war looming once again in Europe, Bromfield returned to Richland County, Ohio with his family. When the snows melted, he found the once fertile farmland ruined by negligent agricultural practices. His mission turned to restoring the abused soil, plundered woodlands, and abandoned buildings. He purchased three old farms and combined them into one. Over time, by replanting fallow fields into grass and the intelligent use of controlled grazing, natural fertilizer, crop rotation, and other organic methods, the fertility of the land was not only restored but also vastly improved. His writing turned more and more from fiction to works on sustainable agriculture. Critics were hard on Bromfield's later novels, but the truth is, his heart was no longer in fiction. He felt he had more important things to attend to and write about, and his later fiction was mostly a financial means to an end - restoring the ruined farmlands he had purchased, recording his experiences, and launching a crusade for sound farming and conservation practices. His farming techniques became as famous as his novels, and the farm drew visitors and agriculturists from all over the world. Every Saturday morning, NBC broadcast his Voice from the Valley radio program. He had a widely syndicated newspaper column and wrote numerous magazine articles. Malabar Farm was drawing 20,000 visitors a year, the high point of which was a Saturday in the early 1950s when 8,000 farmers and their families from 27 states converged on Malabar Farm for Successful Farming Magazine's field day on building topsoil. Restaurants and stores in the valley ran out of food and supplies and traffic was backed up for miles down country roads leading to Malabar. So, although there was always the sprinkling of the rich, the famous, and the intellectual at Malabar, enough to give it a touch of Hollywood mystique, it was the plain people and farmers and cattlemen from all parts of the world who came in droves to share Bromfield's world. Although his ideas were often called radical by agriculturists of his day, Bromfield was far ahead of his time in warning against pollution, chemical-intensive farming and indiscriminate use of pesticides. He promoted contour plowing, crop rotation, wetland preservation, and many other "new" agricultural methods that have become widely accepted and practiced today. Some claim his demonstration of sustainable farm practices saved America from a second dust bowl. Pleasant Valley has been compared to Thoreau's Walden. Bromfield strongly believed that mankind was better off when closely attuned with nature and the earth, that materialism was destructive, and that money and the manipulation of money was a false answer to the problems of mankind.

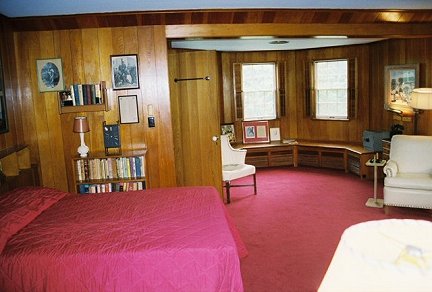

The Books (and Other Writing)Bromfield's first novel was The Green Bay Tree, published in 1924 by Frederick A. Stokes. It achieved great critical acclaim as well as popular success. He subsequently had the financial means to write full-time and followed with Possession (1925), Early Autumn (1926), and A Good Woman (1927). These four novels were interrelated and presented a broad picture of American life at the time, encompassing the growth of industrialism and resultant turning away from pastoral and agricultural roots, and the turmoil of war. He depicted independent, strong-minded women in his novels, and his stories carried some of them back across the ocean to Europe. Seven of his books were made into films, including The Rains Came and Mrs. Parkington, starring Greer Garson and Agnes Moorehead (1944). The movie Night After Night (1932) was adapted to film from Louis Bromfield's Cosmopolitan magazine story, "Single Night" and featured the debut of Mae West in her first talking film. His books have been published in 27 languages; 8 of his books were top ten U.S. best sellers. He wrote over a dozen screenplays, including Brigham Young - Frontiersman (1940), It All Came True (1940), and The Life of Vergie Winters (1934). It is a little known fact that Bromfield contributed some of the dialogue to the classic film Dracula (1931) starring Bella Lugosi. Bromfield also wrote the script for Walt Disney's The Vanishing Prairie. The very successful Walt Disney cartoon Ferdinand the Bull was a collaboration between Walt Disney and Louis Bromfield. They adapted the children's book The Story of Ferdinand by Munro Leaf; Bromfield wrote the script and Disney oversaw the animation. Disney later selected animation cells from the making of the film and sent them to the Bromfield daughters in 1939, and they still hang on the wall in the children's play room. While he was working at MGM, Samuel Goldwyn assigned a man named George Hawkins to do Bromfield's typing. They hit it off, established a good working relationship, and became good friends. When Bromfield left MGM, he took George with him to be his personal secretary and business manager and set him up with an office and room in their house in France. Over the years, he became part of the family. When they moved to Ohio, George wasn't too eager to live in "the middle of nowhere." To persuade him, they constructed a special living area upstairs at the Big House that was closely modeled after George's room in the St. Regis Hotel in New York City. Bromfield even painted him a picture of the New York City skyline to hang in his room. He stayed with the family for the rest of his life.

Bromfield had traveled widely throughout Europe and some of Asia, and he developed strong political views based on his observations. His pamphlet England, A Dying Oligarchy (1939), was an attack on the reluctance of the British government under Prime Minister Chamberlain to confront Hitler and Fascism in the time leading up to World War II. He strongly condemned those who put profits and market ahead of human values and leaders who lacked the integrity to take command of the situation. Bromfield came under criticism for his sharp words in this publication. Even though he was proven correct - and eventually Winston Churchill emerged as the crucial type of leader whom he invoked - the publication of this pamphlet wreaked havoc on Bromfield's reputation at the time. A New Pattern for a Tired World, Bromfield's ambitious socio-economic work published in 1954, bears looking at today. In it he writes about conditions around the world, politics, history, wars and causes of war, distribution of wealth and resources, and so much more. Reading it now, you may see evidence of missed opportunities and repeated mistakes in the 52 years that have passed since its publication, but perhaps here are also many ideas that can still be put to good use. Once again, in many ways, Bromfield was ahead of his time. With thoughts that had been developing in his mind after the world had been exhausted by two world wars and with Communist expansion becoming a major fear, he bravely set forth suggested socio-economic solutions and strongly criticized our attempts to interfere militarily around the world in endeavors to force democracy on people who are unprepared to understand it, let alone desire it. He points to our lack of knowledge when it comes to understanding the reality of circumstances in other countries and cultures. He sets forth ideas on leading by example and on cooperation and free trade that could benefit even the smallest and poorest of countries and advance their cause as well as our own. He later wrote his mostly autobiographical book, From My Experience and, in the last year of his life, Animals and Other People, in which he shared his appreciation for the personalities and intelligence of individual pets and animals he had known. Bromfield's wife Mary died in 1952. His right-hand man George Hawkins passed away at the age of 49 in New York City in 1948 while on a business trip for Bromfield. Eventually, Bromfield moved upstairs into George's old quarters and invited some of the farm hands to move into the extra rooms of the Big House. In the early spring of 1956, Bromfield collapsed while working in one of his fields. He was taken to University Hospital in Columbus, Ohio where he was diagnosed with bone cancer. He died in the hospital about two weeks later on March 18, 1956 and was buried in the cemetery on the farm next to his wife Mary. The inscription on his gravestone reads: "To him who in the love of nature holds communion with her visible forms, she speaks a various language." (William Cullen Bryant)

|