|

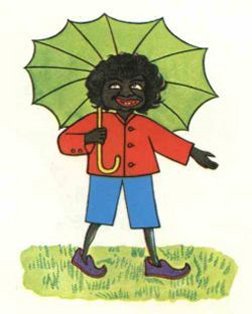

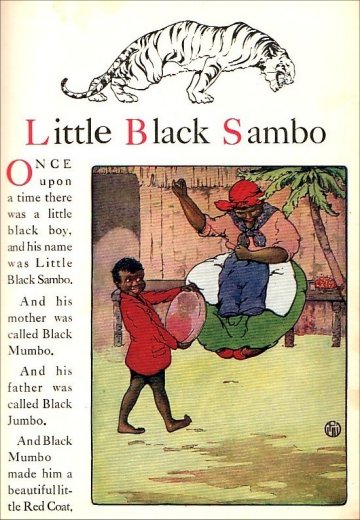

"It was the best of times, it was the worst of times ..." So began Charles Dickens' classic novel, A Tale of Two Cities. The same could be said of a classic children's book, whose innocuous beginnings have spawned more than a century's worth of debate, dialogue and controversy. That book is, of course, The Story of Little Black Sambo. It's a good story as far as storytelling goes - one in which a little Indian boy is chased by tigers and has his colorful clothes taken but ultimately survives to not only retrieve his clothing but eat 169 pancakes flavored with butter made from quarrelling tigers running around a tree. Written and illustrated by Helen Bannerman, the book made its first appearance in England in 1899, followed shortly thereafter by an American edition in 1900. Since that time, it has enjoyed numerous reprintings, has been widely translated and, for many years, was considered a classic of children's literature. Helen Bannerman wrote the book for her own children while living in India as the wife of an English Army surgeon at the turn of the 19th century. While Mrs. Bannerman shuttled back and forth on long train journeys between her husband, who was busily investigating the causes of bubonic plague, and her two sheltered daughters, she composed little stories for the children's amusement. From such noble pursuits arose the tale of Little Black Sambo in 1898, from which Mrs. Bannerman created a little book, illustrated and bound by herself. Alice Bond, an English friend of Mrs. Bannerman, was captivated by the story and, believing that it should be published, brought the text and illustrations to London. Grant Richards, a seemingly unscrupulous British publisher, acquired the copyright for a mere five British pounds and promptly published the book in 1899 as the fourth volume in his Dumpy Books series. It enjoyed immediate popularity due to its clever story and innovative small format, sized just right for children's hands. However, Grant Richards failed to protect the copyright. Within a year, Frederick A. Stokes had published the book in the United States, where it was subsequently reprinted in magazines, storybooks and numerous unauthorized editions - many with rewritten texts and new illustrations. Not only published as a stand-alone book, Little Black Sambo was featured regularly in collections of children's stories, compilations of fairy tales and similar children's anthologies. So widespread was the story's popularity among children that, according to an article in The New York Times dated October 22, 1931, "Perhaps every child starts out with Mother Goose and Little Black Sambo...." While the book was initially regarded as a childhood favorite, by the mid-twentieth century, Little Black Sambo became an object of heated debate as racial consciousness grew. Educators recommended that the book be removed from library shelves, while others staunchly defended the book as a lovable staple of childhood and the harmless victim of its own era. The setting of the book in India and its use of Indian characters was touted as a counterpoint to the arguments of racial stereotyping. Nevertheless, Bannerman's use of thick lips, rolling eyes and frizzy hair in her illustrations of Little Black Sambo led to charges that the book was offensive to African-Americans, along with her use of the name Sambo, which had a long history in minstrelsy. As early as the 1830s, a song titled "Sambo's Address to his Bred'ren" was performed in American minstrel shows. Such shows traditionally used white performers in blackface to caricature Southern blacks as a highly popular form of entertainment. Complicating the racial issue were the many unauthorized American editions resulting from British publisher Grant Richards' failure to secure the copyright in 1899. The story often appeared in American editions with illustrations other than the original Bannerman pictures. In the 1920s, 1930s and 1940s, the book was commonly illustrated with characters that appeared more African-American than Indian, and the setting was sometimes eerily reminiscent of a Southern plantation, rather than an Indian jungle. The cover illustration of the original Bannerman version shows Little Black Sambo attired in red shirt, blue trousers and purple shoes.

However, by the time Favorite Nursery Stories was published by Saalfield Publishing Company in 1920, the anthology's opening illustration of Little Black Sambo depicts a barefoot child with distinctly pickaninny overtones and his mother, Mumbo, bears a striking resemblance to Aunt Jemima.

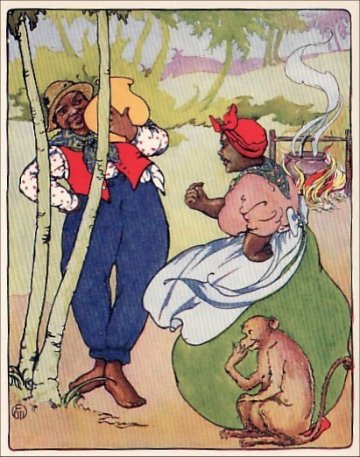

Also, in the 1920 American Saalfield version, the illustration of parents Mumbo and Jumbo evokes the image of slaves working on a plantation, despite the presence of palm trees and a monkey.

By the mid-twentieth century, The Story of Little Black Sambo had fallen into disfavor among many educators and purveyors of children's literature. The New York Times reported on February 5, 1956 that Toronto's Board of Education had ordered the removal of Little Black Sambo from bookshelves in the city's schools "... after hearing complaints from a Negro delegation that the 58-eight-year-old children's favorite was a cause of mental suffering to Negro citizens in general and children in particular." It should be noted that a number of Canada's leading librarians decried Toronto's book ban, citing the long history of the book as a favorite of children. Nevertheless, bans of Little Black Sambo escalated as school districts throughout North America followed suit. In the decade of civil rights marches and desegregation, The New York Times reported on October 20, 1964 that schools in Lincoln, Nebraska had banned the book and ordered it removed from school libraries. As the 1960s unfolded and race consciousness led to the demise of Little Black Sambo as a mainstay of children's literature in America, anthologies that featured collections of favorite children's stories were no longer including Little Black Sambo among their literary selections.

>>>>>Click here for page two>>>>

Questions or comments?

| Forum

| Store

| Publications

| BookLinks

| BookSearch

| BookTopics

| Archives

| Advertise

| AboutUs

| ContactUs

| Search Site

| Site Map

| Google Site Map

Store - Specials

| BookHunt

| BookShelf

| Gold Edition & BookThink's Quarterly Market Report

| DomainsForSale

| BookThinker newsletter - free

Copyright 2003-2011 by BookThink LLC

|

|

|