|

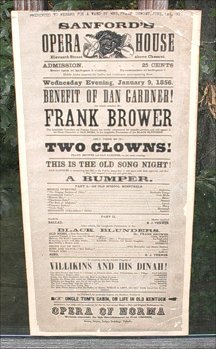

In 1860, on the eve of the Civil War's outbreak, non-enslaved black Americans comprised only 1.5% of the total American population - a total of 4.4 million out 31 million. Out of that 4.4 million, less than half a million, or 476,748 blacks, were identified as free men or women in the 1860 national census, while 4 million slaves were recorded. Images of slaves are very rare, and only a special relationship with an owner would have warranted an individual portrait. While the slave population was viewed as integral to the economy of America, particularly in the tobacco and cotton industries predominant in the Southern states, few slaves were photographed and even less had portraits that survived the condition problems endemic to antique photographs. For this reason, as noted in Part I of this ongoing series on Civil War ephemera, African-Americana, along with ephemera associated with Lincoln and the Confederacy, typically command the upper echelon status in price and desirability among Civil War collectors. However, based on my own experience, many examples of collectible Civil War African-Americana still exist in the marketplace and can be found at antique stores, estate sales and local auctions at prices that allow one to resell at a profit. Most booksellers are familiar with Uncle Tom's Cabin, the groundbreaking book by Harriet Beecher Stowe that burst onto the literary landscape in 1852. According to Printing and the Mind of Man, edited by John Carter, "Into the emotion-charged atmosphere of mid-nineteenth-century America, Uncle Tom's Cabin exploded like a bombshell ... the social impact of Uncle Tom's Cabin on the United States was greater than that of any book before or since." Harriet Beecher Stowe, a 40-year-old wife and mother descended from a lineage of preachers and abolitionists, was inspired by moral outrage over the Fugitive Slave Act of 1850, which required all citizens to return runaway slaves to their owners. She penned her story based on a disturbing inner vision of a slave being beaten to death by his master and her work was serialized in "The National Era," an abolitionist newspaper, beginning in 1851. The story was embraced by an eager public and, on March 20, 1852, Uncle Tom's Cabin was officially published as a two-volume book. Over 10,000 copies were sold in the first week; by the end of the year, 300,000 copies had been sold in the United States alone. The first printing was issued as two volumes in three formats: printed paper wraps (first issue) at $1.00, cloth binding (second issue) with a central vignette in gilt at $1.50, and a more elaborate "gift" binding (also second issue) with gold stamped border and gilt page edges at $2.00. The second printing bore the designation "Tenth thousand," and subsequent printings were labeled with ever-higher numbers. Within two months, the first London edition was in print. [EDITOR'S NOTE: The London (Cassell) edition is sometimes cited as the first appearance, but BAL states that the Clarke and Co. edition was advertised six months earlier than the Cassell.] There were 14 German editions published in 1852, and by 1853, 17 French editions and 6 Portuguese editions appeared. By 1879, Uncle Tom's Cabin had been translated into 37 languages. The popularity of the book inspired numerous theatrical presentations. Uncle Tom's Cabin was first dramatized in Baltimore in 1852, even before the two-volume book had been published and while the serialization was still ongoing. The famed George Aiken stage adaptation of Uncle Tom's Cabin followed in 1853 and, soon after, "Tom Shows" sprouted all over the country. It is estimated that, for every one person who bought or read a copy of the book in the 19th century, 50 people saw the stage play. Due to the copyright laws - or, rather, a lack of them - in 1852, Harriet Beecher Stowe owned only the U.S. rights to her novel and she had no control over the characters she created. Her Calvinist upbringing precluded her from supporting the theatrical shows, and vast liberties were taken with the novel to suit the intended audience. Stage shows in the South tended to support slavery, while those in the North had a pro-abolitionist slant. The plays degraded the novel's themes, and the book's characters took on the aura of racial caricatures. Song and dance sequences interspersed melodramatic scenes with blackface minstrelsy. Thomas D. Rice, who created the "Jim Crow" dance, played Uncle Tom in a prominent New York stage production. Many productions featured recent songs by Stephen Foster, including "My Old Kentucky Home." The Civil War years saw the rise of theatrical troupes performing "Tom Shows" and, as late as 1890, an estimated 500 stage shows were touring the country. Such shows were also popularly known as "Tommers." Last summer, I happened upon an unusual pre-Civil War broadside for a minstrel show performance held on January 9, 1856 at Sanford's Opera House in Philadelphia, advertising Frank Brower performing as "Old Mush" in a performance titled "Black Blunders." I found the broadside at a local Maryland auction and acquired it at a reasonable price.

Frank Brower was an American blackface performer who began his career in circuses and theaters. He teamed up with three other blackface performers - Dan Emmett, Richard Pelham and Billy Whitlock - to form the first organized minstrel troupe in the early 1840s. They called themselves the Virginia Minstrels. Playing the banjo, fiddle, tambourine and bones, the four men each performed on a different instrument and mixed their music with comedic skits. In 1854, Frank Brower took the role of Uncle Tom in the Bowery Theatre's stage play of Uncle Tom's Cabin.

>>>>>Click here for page two>>>>

Questions or comments?

| Forum

| Store

| Publications

| BookLinks

| BookSearch

| BookTopics

| Archives

| Advertise

| AboutUs

| ContactUs

| Search Site

| Site Map

| Google Site Map

Store - Specials

| BookHunt

| BookShelf

| Gold Edition & BookThink's Quarterly Market Report

| DomainsForSale

| BookThinker newsletter - free

Copyright 2003-2011 by BookThink LLC

|

|

|