|

Sourcing Inventoryby Craig Stark 6 February 2023 |

How to Turn a $5 Book Into a $150 Sale

Shortly After Publishing last month's newsletter, I received an email from a subscriber asking me if I would write something about sourcing inventory. It's

certainly one of the more talked about bookselling topics out there, and I've written a number of articles about it myself, primarily in past Gold Editions. But,

how about something new on it - and free? I should warn you, however, this is an angle you might not expect to hear. Or want to.

First, since I was a fledgling bookseller once, I still recall times when I labored under a few notions about how to go about this book biz before realizing,

ultimately, that I was getting it all wrong - maybe not all wrong but mostly wrong. Perhaps the most debilitating notion of all was that, since books are "everywhere,"

buying books for resale was primarily a matter of locating secret or under-shopped venues and exploiting them. Then, once the acquisition spigot was turned on, you

built up inventory numbers until a steady flow of income could be established. Anybody who has ever visited a bookseller's forum or other group has surely seen

this question: How many books do I need to get listed to make a living at this? As if it was nothing more than a numbers game.

You could sort of get away with this approach 25 years ago, at the dawn of the online-venue age. 15 years ago? Not so much. Now? Not. Now we live in the

attics-have-been-long-since-cleaned-out era, when this approach often leads to nothing but frustration. Technology - e.g., bar code scanners - may help some, but if

you source locally in even a somewhat competitive area, you'll likely be helping tech vendors out more than yourself. What's more, if you're seeking nothing more

than a magic inventory number representing essentially ISBN-era books, sit back and watch your books plunge in value as soon as you acquire them. If not now, six

months from now. What sector of the used book market experiences the most rapidly eroding values? $10 and under. The second most? $20 and under. And so on. This

has always been the story: If you focus on nothing more than building up the size of your inventory, it's a loser's game. However, if you focus on raising your ASP's,

the magic starts - and will stand you in good stead for as long as you sell books in any era. Don't know what an ASP is?

Average.

Selling.

Price.

This begs the question, of course, how do you source-higher value books? Years ago, there was a prominent bookseller who participated on one of the more active

bookselling forums. At times he was bracingly transparent. He would divulge not only where he purchased his inventory (mostly at auction houses) but also what he

paid for the items. In turn, these same items could later be viewed as his sales. The term for this is arbitrage. His outcomes - the gaps between what he

paid for something and what he realized - were consistently stunning. And get this: Several times he divulged everything in advance, both what he was planning

on bidding on and where, and when. It was a beautiful illustration that you could hold somebody's hand, walk them through how you bought and sold books, step by

step, and still not be the least concerned about them stealing any "secrets."

There's more.

Somebody once asked him what he specialized in, also how best to pick a specialty. Though his words were written and not spoken, they still ring loudly in my ears: It's

a matter of taste. Taste? The first question that popped into my head was: Are you saying that the only criterium for purchasing inventory was whether or not it suited one's

taste? That was exactly what he was saying. Before you dismiss this as another hackneyed iteration of what so many self-help gurus would say - e.g., "Do what you love, and

you'll succeed" - I invite you take it one step further, which so few seem to do. When you buy something that suits your taste, a window opens into the inner sanctum of the collector

who collects it. Your buyer. You know what the fuss is about. Why it's important. And most importantly, you know how to sell it.

If you pay close attention to this phenomenon, you can see it play out from the other end. You can get a feel for how collectors collect. The trigger isn't scoring bargains;

it's fulfilling a need. The longer they collect, it's more likely that what they haven't found yet has deepened a need. And often, for whatever reason, it's hard to find. And

more valuable to them. And even if it isn't hard to find, maybe other booksellers don't know how to push the right buttons. Money matters to collectors, sure, but not necessarily

so much.

I've always loved case studies. They have a wonderful way of moving from the abstract to the particular. Let's look at a particular item that perhaps many of you have

encountered with some regularity:

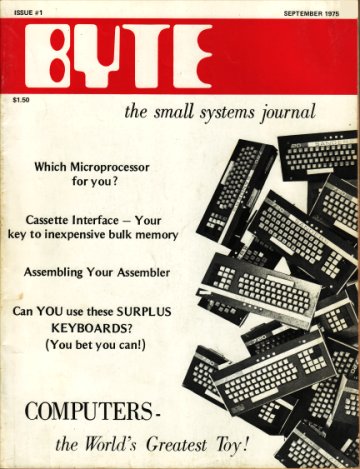

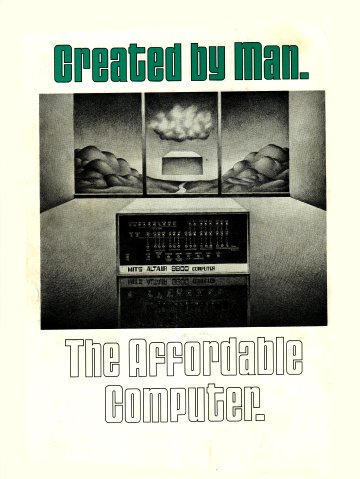

BYTE: the small systems journal launched publication with this, the September 1975 issue, 96 pages strong. To put this in perspective, Bill Gates and Paul Allen founded

Microsoft on April 4, 1975 shortly after programming a BASIC interpreter for the recently introduced MITS (Micro Instrumentation and Telemetry Systems) Altair 8800 microcomputer.

This computer appeared prominently in an ad on the back cover of BYTE and was featured in many forthcoming ads.

It's no exaggeration to assert that these three developments, more than anything else, launched the personal computer revolution. The Altair 8800 was affordable, had a microprocessor

powerful enough to actually accomplish meaningful tasks, including business applications, and soon became the darling of the PC market despite being primarily available only in

kit form. Most of us know about Microsoft, then and now. And BYTE? By the 1980's BYTE had evolved into a dominant PC publication hundreds of pages long, over ½" thick and capturing a

breathtaking ad revenue. Oh - and guess who published Microsoft's first ad?

The Altair 8800 is no more, of course, and you'll need to fork over thousands to buy an original machine, and BYTE has also bit the dust. But back issues of BYTE display an

interesting phenomenon. Not only were the early issues historically groundbreaking but they also emphasized the do-it-yourself approach and dug deeply into technical theory and

applications.

And here's where it gets even more interesting for us. 50,000 of these BYTE premier issues were printed. What does your gut tell you about this number? How could they possibly be worth

anything? True enough, I've seen issues go for $5 or less, especially when purchased in groupings of early issues. However, if you subscribe to historical pricing services, you'll

also note that they have, on more than one occasion, sold for as much as $150 - and fairly often for over $100.

Is this a golden opportunity for arbitrage? Yes, but. Look over a handful or so of these issues presently for sale, note how scant the descriptions are, how many aren't even accompanied

by photos - and most of all, how none get into any detail about why the September issue is important. Here's the takeaway: If you're willing to take the trouble to build value into

your products by getting into this very detail, guess what you can do? You can buy copies of this magazine for a few bucks each and post your results in public. You can even announce

that you're going to continue to do this, and you will still out-perform your so-called competition.

Think about this. What would you rather do? Look endlessly for inventory sources that are either gone or going away? Or learn how to build value into readily available books that invite,

if not beg you to build value into them?

Questions or comments?

< to next article

Contact the editor, Craig Stark

editor@bookthink.com