A Brief History of Publishers' Weeklyby Craig Stark #156 30 May 2011

|

And Why It Matters to Booksellers

Publishers' Weekly (now Publishers Weekly) commenced publication in 1872, a whopping 139 years ago, and despite a recent shake up or two, still cranks out 51 issues annually. PW was originally conceived as a "catalogue" for publisher's to announce upcoming publications to booksellers (and otherwise draw attention to them). In the summer of 1874 at a publisher's convention in Put-in-Bay on Lake Erie, PW was established as the official organ of the book trade, and from that point forward it gradually expanded its content to include general book trade news and many related features.

Why should this matter to us? If you've read much about Book Publishing history in the United States and peeked at the author's sources of whatever book you happened to be reading, you've no doubt noticed that time and time again PW is cited as a primary source. Sure, there is no shortage of specific publishing house histories and book-related publications, but it's hit and miss. Some major publisher's have had no histories published; others have but they encompass only a portion of their histories, say, when an especially influential editor was at the helm or are essentially nothing more than informal memoirs woefully bereft of anything useful to us. Many book-related publications have a narrow focus or have more used to collectors than booksellers. But the continuous publication of PW from 1872 forward has provided us with nothing less than a comprehensive, detailed history of publishing itself, including much information on major publishers (and many not so major) in the book trade, specific historical information about the books they published and much, much more.

The usefulness of a searchable database of PW back issues can't be overstated. How many times, for example, have you come across a ca. late 1800s or early 1900s book with scant or no publication data, perhaps not even a date, and been frustrated in your attempts to identify, let alone catalog what you have so as to present it for sale? I have more times than I can count. But in the absence of a relevant bibliography (which either doesn't exist or isn't readily available) here's where PW can prove very useful indeed. A search of the book's title can often bring up mentions in PW, and sometimes you can snag an illustration of the book in a publisher's ad (occasionally showing a dust jacket you don't have - and in fact you may have assumed it wasn't issued with one!), often the specific month and year it was first published or reprinted in some form, its price, and occasionally the number of copies printed or sold or both. Or, failing this, there might be a publisher's address in your book but not a publication date, and by searching for mentions of the publisher in PW, you can narrow down, sometime pinpoint, the date of publication based on the address alone. Given how often publishers, especially in this era, changed owners, names and locations or merged with other publishers or whatever, this isn't as far-fetched as you might think.

The possibilities for establishing the publication details and histories of specific books are many, and the hunt for relevant information, once you learn how to proceed efficiently, can be great adventure. And - you can do a lot of this online, free.

A good place to start is the

Internet Archive. This will present a list of all public domain PWs available for viewing online or download via Google. PW was formatted into two volumes annually, January-June and July-December. Currently, most of the issues from Volume III (January-June 1873) through Volume CII (July-December 1922) are available - nearly 50 years worth.

You will notice that there are several formats available. PDF is great, of course, because you can view the actual images of the pages, but this particular species of PDF isn't searchable; the text version is, but unfortunately, the text version includes a lot of garbage and sometimes outright errors generated by the OCR process and no images whatsoever. So - you can search the text version with your keywords, establish the issue the results are in, and go to the PDF version. You can also search directly at Google Books, and in some (but not all) cases this will take you to the PDF page(s) you're looking for. Or a snippet.

Newer, post-1922 issues of PW may be available at your local library in print or microfilm versions or in some cases may be purchased in print online.

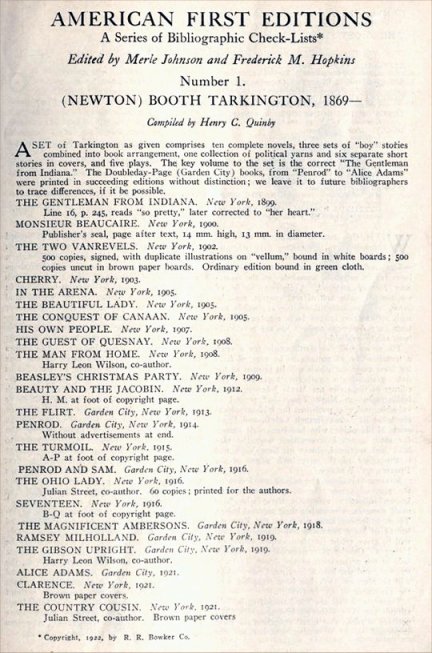

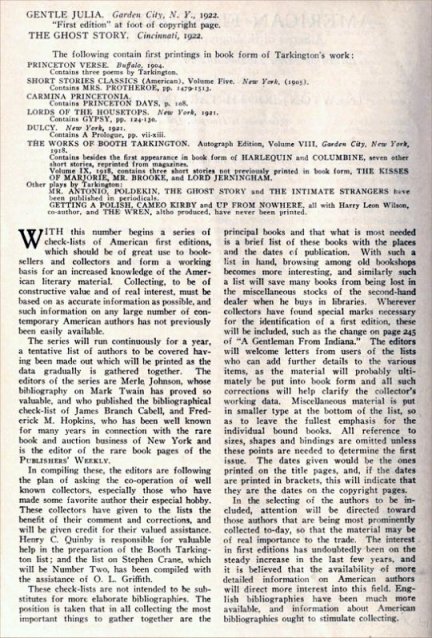

There is a treasure trove of additional information in PW as well, much of it relevant to the bookselling cause. You may not know that Merle Johnson's

invaluable reference American First Editions began its life as a series of checklists published in PW:

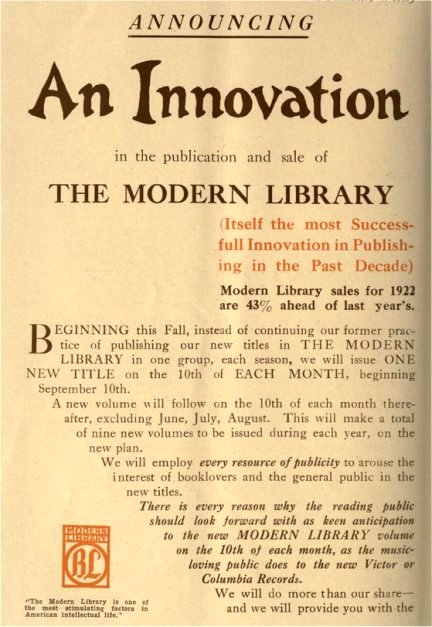

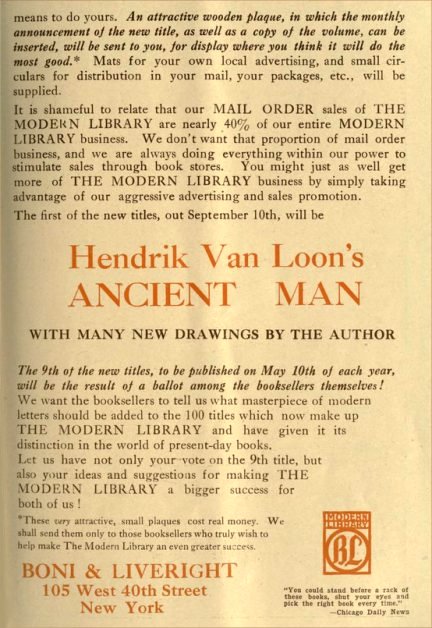

Modern Library collectors who are seeking information on publication dates would likely be interested in the following PW announcement:

And I bet that one of those wooden plaques would be a profitable find!

One could fill multiple volumes with PW content that would be useful to booksellers. I highly recommend spending some time not only searching the archives but browsing them too. You never know what you're going to run into. Here's something from a ca. 1922 issue, for example, that echoes into modern times and could be classified in the "Some Things Never Change Dept."

Reminiscences of a Book Scout

By Joseph Jewett Barton

XI. Reflections on Monday

The other day I was sitting in front of my desk with my feet on it, wondering whether business was really dead or only sleeping.

An old friend came in, drew up a chair, pulled out a smelly pipe, and, after getting it working well, started to soliloquize. "Yes, you had a copy of 'English Notes, intended for very Extensive Circulation, by Quarles Quickens, Esq., 16 pp. Boston Daily Mail Office 1842.' It had salmon pink wrappers, was a nice copy. Perhaps you picked it up for fifteen cents. You didn't tell me anything about it, but sent it to a New York dealer and probably asked about fifty dollars for it. I wonder if you saw that article in Hopkins' page in the Publisher's Weekly where the 'Notes' was attributed to Poe and lately had been sold at auction for eight hundred dollars, and that the next copy would probably bring a thousand." As he went out the door, I heard something about "A guardian--be careful when in the rural districts that the cows don't bite you."

I got to thinking about that tragedy. It isn't the money loss, but the sting of not knowing the value. Sombre thoughts breed others, and as various experiences of the less pleasant kind passed thru my mind, I recalled the passing of old Mr. Brown. Brown was not his name, but at present I cannot remember his real one, if I ever knew it.

He was tall and spare, a little bent in the shoulders, had dark curling hair, streaked with gray, of more than the customary length, and wore a thin mustache and beard. He looked like an old time print of a master of a small red school.

When I became well acquainted with him he told me much of his life. As I recall it, his family had not been very prosperous, nor of any particular station in the small Now England community in which he was reared. He had worked his way thru college, with intervals of teaching school to secure needed funds to finish his course.

I suppose too little food and too much hard work had undermined his powers of resistance, so at some time he had drifted into tuberculosis, but was now considered cured.

He kept a little book shop way out toward the end of the busiest street in Brooklyn. As I never pass by any place that has books in the window, I of course went in to see what he had of interest. We, of the craft, prefer to seek our own and wait on ourselves, but Mr. Brown was eager to show me everything in his little shop; he seemed fearful lest I might overlook something.

He had a hobby--Italian poetry of the old school in the original--there is a subject for you. He talked earnestly, lengthily and finally boringly on the subject; when you are hoping you may find a Thompson's "Long Island" or the "History of Flatbush" tucked away in a dark corner where somebody else may have overlooked it, the subject of Italian poetry, however fervently presented, doesn't seem to touch the spot.

I wound up my first visit by buying a "Pilgrim's Progress" with Anderson plates; that's all I could find, and I had to buy something.

Brown asked me if I would manage his shop for a few minutes while he went across the street to the baker's. He said he had not breakfasted yet, and I surmised that the thirty-five cents I gave for Bunyan was immediately converted into a bottle of milk and some buns.

I formed the habit of stopping in to see Brown about once every week. He was a gentleman, was well educated, very poor and of indifferent health. He didn't whine or curse his luck or the Capitalists, but did the best he could with what he had. He should have had many a bottle of milk and other nourishing food every day, but I do not believe he got it. He did not appear to have any relatives or friends, tho he did say he had some books in his trunk that were to go to a friend when he died. He promised to show those books to me, merely to gratify the desire of seeing a few nice items, but he never did.

In the course of one of our conversations he inquired as to my own likings among hooks; I told him I had an insane desire to acquire, at a moderate price, a presentation copy of a Kilmarnock Burns in the original boards, uncut, but I did not think my longings would ever be satisfied. Then in the most unsophisticated way he remarked that he knew an old Scotchman from whom he could get a Burns, whether first edition or not he couldn't say, as he was not interested in poems in the Scottish dialect. It was a very old copy, and he would go and see him in a few days and the next time I came, he would, in all probability, have it for me.

For many weeks he joined me in breakfast from the bakers, and if he had taken on the weight that I did from that second breakfast of mine, he would still be with us.

As time went on and he hadn't seen his Scotchman, and was not making any apparent effort to do so, my enthusiasm waned a little and I went off on a fishing trip. It was probably a month before I got around to Brown's shop again, and them it was closed. I thought nothing of this, and called again in about another week-still closed.

A few days later I was in a book shop and asked the proprietor, "What has become of Brown--perhaps you know him, he keeps a little shop out toward the end of your street"

"Who, Brown?" he replied. "Yes, I knew him, he is dead."

"What was the matter with him?" I asked. He told me that the old man's neighbors had missed him for several days, had notified the police and upon breaking into his store had found him dead, laying over a trunk full of books. The coroner said he died of starvation.

I have no doubt he was glad to go, but somehow I felt guilty. It seemed as tho there were something I had failed to do.

And tomorrow, it being Tuesday, I will get a large bunch of mail, perhaps, and after I have separated the checks from the bills, I will cash them and then go and buy among other things, several copies of "English Notes." Certainly among all those pamphlets in the second story of that old barn I have just learned about there ought to be at least two more.

Copyright 2003-2011 by BookThink LLC