Hidden Profits in Public PlacesBooksellers as Teachersby Craig Stark #169 17 February 2014 |

Everybody has to start somewhere, and typically, with the inevitable exceptions, those few who become famous for what they do don't do so overnight. Years of

obscurity often precede their making it big. As booksellers, we can cash in on this phenomenon - if we know what to look for and if we, in turn, market things so as to

showcase what we've found and explain why something is important. As in so many other professions, the most successful booksellers are often the best teachers; and

in this context, our students are book collectors.

Funny thing about people who teach as a profession: They almost always have sizable libraries. And so it should be with booksellers who make it their business to

teach. New discoveries in our profession are far surpassed by discoveries that have already been made. And written about. It's just a fact of life that most of the knowledge

we acquire is derivative: We've learned it from somebody else.

This is one reason why bibliographies are so important. Not only do they show us how to identify the obviously valuable First Editions - the things most everybody is looking

for - but they also, usually, document what preceded an author's fame. The less obvious, sometimes hidden stuff. This is where teaching - and profits - can kick into high gear.

Take J.D. Salinger. He is often described as a one-book wonder, and yet The Catcher in the Rye represents only a small part of his writing life, both after its publication

and, most importantly, before.

Here's a slender, unassuming book that I bet will not be found in most of your reference libraries:

A slight 62-pages long, and yet time and time again I've profited from its modest contents. The Catcher in the Rye was published in 1951; bibliographer Kenneth Starosciak cites

fully 29 appearances that preceded it. Among these are articles or stories in magazines that are household names - Collier's, Cosmopolitan, Esquire, Harper's,

Good Housekeeping (of all things), Mademoiselle, The New Yorker, Saturday Evening Post, and so on.

Think about this for a moment. Mid-century magazines that had large circulations are usually ho-hum, low-value things, and if there are exceptions, it usually has to do with what's happening

on the cover, say, a photo of Marilyn Monroe. Again, this is the obvious stuff. Think also about this: How many times have you seen a listing for a magazine that fails to mention

significant content? It happens all the time.

Now consider the Salinger collector. Apart from Catcher there are only three books remaining to collect - Nine Stories, Franny and Zooey and Raise High the Roof Beam, Carpenters

and Seymour: An Introduction - and these are compilations of short stories or novellas. And - all of these books are plentiful enough to acquire quickly, if not cheaply. What's a poor

Salinger collector to do next?

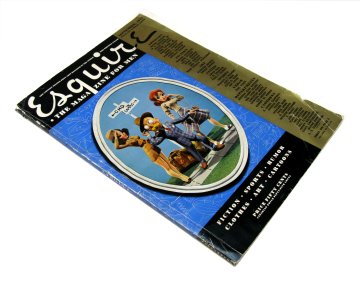

Here's a magazine I picked up recently on eBay for a few bucks:

First, note the date - September, 1941. This is darn early in Salinger's career. There were only a few appearances in print that preceded it, and these were almost entirely

in small circulation literary magazines. Second, the funny thing about this is that, though Salinger's name appears in bold black ink in the contributor list on the right side of

the front cover, the seller failed not only to mention his appearance but also failed to provide a clear photo of the cover. Thanks to Starosciak's bibliography,

however, I knew what was what immediately - and when I get around to selling this thing, you can bet the farm that it will be a teaching moment, not to mention a three-figure outcome.

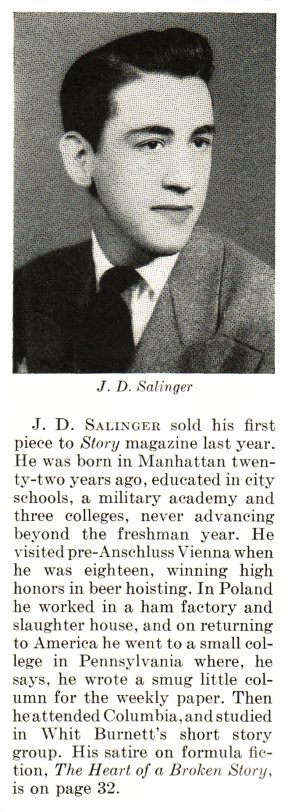

And finally, part of this teaching will include this:

Those who know the reclusive Salinger know he was loath, especially later in his career, to allow publisher's to use any photo of him whatsoever. This photo, which appears

in the "Backstage With Esquire" feature in the same issue, is both early and rare - in fact, it's the most significant selling point of the magazine.

Copyright 2003-2014 by BookThink LLC